by Alex Robertson†

Introduction

Esports has quickly become one of the world’s most popular, and valuable, entertainment and multimedia fields, surpassing over $1 billion in revenue in 2020.[1] One major part of this growth has been the evolution of where value lies in the industry, and the surging relevance, economic, and legal importance of brand protection.

Even only a few years ago, the large recognized “brands” in the esports industry were primarily AAA[2] game producers, goods manufacturers (hardware, software, ancillary goods), platforms which transmit/host/broadcast content, and potentially a select few high profile esports teams, and even fewer individual players. However, now individual players, content creators, streamers, commentators, esports teams, gaming orgs, and multi-channel networks, are all recognizable and valuable brands.[3] Despite this, trademark protection is still very rare in this field. Of the top 20 most watched Twitch.tv (“Twitch”) streamers, less than half have any trademark protection.[4] With this growing recognition, and subsequent value and power, it is an increasing imperative that gamers understand their intellectual property rights in their brand. Even more important however is understanding also how to utilize those rights to proactively protect themselves, and fully exploit, monetize, and benefit from those rights.

This article will discuss the importance of trademark rights in the esports field, particularly protecting gamertags, team names, and other brand identifying features. Section II will provide a general explanation of trademark law, and Section III the process of obtaining a trademark. Section IV will explain the benefits a gamer or team could have from registering their trademark. Additionally, this article will briefly look at trademark usage in the industry, give examples of high-profile individuals who made mistakes in this process, highlight their consequences, and illustrate some positive examples in the field.

I. Trademark Law Basics

A. What is a Trademark

A trademark is any word, name, symbol, or design, or any combination thereof, used in commerce to identify and distinguish the goods of one manufacturer or seller from those of another, and to indicate the source of the goods.[5] In essence, a trademark will indicate who provides or sells a good or service. Trademarks protect words (wordmark), or logos or designs, which can be a combination of words and design elements or solely design elements (stylized marks). In the context of esports, this means that there would be separate trademarks, one for a gamertag as well as a unique gamer logo (if one exists), which each require a separate application.[6]

Trademark owners generally have the right to exclude others from using the same or similar mark on the same or similar goods or services in the marketplace.[7] The ability to offer goods or services connected to an exclusive trademark, that no one in the marketplace can copy, is what allows trademark owners to build up “goodwill” or value in their mark[8]. For example, one of the reasons people purchase brand name products over generic products is because of the “goodwill” associated with that brand, whether that be product quality, market recognition, customer service, corporate ethos, etc.[9] With some of the most essential streams of income for esports athletes and teams being official websites, merchandise, and content on social media platforms, it is crucial that athletes and teams have an exclusive right to offer their goods and services through these platforms in connection with their brand identity.[10] To be eligible for protection, trademarks have two main requirements: the mark must be distinctive,[11] and must be used in commerce.

B. Distinctiveness Requirement

The first requirement, “distinctiveness,”[12] looks at the mark’s ability to be distinguished from the goods or services relates to. The distinctiveness of a trademark is broken down into four categories: arbitrary/fanciful, suggestive, descriptive, and generic.[13] On one side of the spectrum, a mark would be considered “arbitrary/fanciful”[14] if the mark has no connection to, or does not describe, the goods or services it is associated with (e.g.: “APPLE” for computers[15]). An arbitrary/fanciful mark is considered inherently distinctive and would be granted exclusive protection based on priority of use. “Suggestive” marks, while still distinctive, are slightly down the spectrum in that it contains a characteristic of the goods/services it is associated with (eg: “NETFLIX” for digital movie rentals).[16] A “descriptive” mark describes the goods or services it is associated with, and will be entitled to protection if it has some “secondary meaning”; if it is a famous or widely recognized trademark in the eyes of the public. (e.g.: “HOLIDAY INN” for hotel services;[17] the mark potentially describes the services, but the mark is also widely known to indicate a specific hotel service). Secondary meaning is also required when protecting a personal name or geographic location as a trademark. Finally, “generic” marks directly describe the goods or services they are associated with, and will never be allowed trademark protection (e.g.: trying to trademark “APPLE” for apples.[18] Trademarks cannot be used to give people monopolies over common terms).[19]

C. Use in Commerce Requirement

The second main requirement for trademark protection is that the mark is “used in commerce,” meaning goods or services are sold or offered for sale in connection with the mark.[20] If at the time of application a trademark has not been “used in commerce,” the applicant can still apply for an “Intent to Use” application, so long as they have a bona fide intent to use the mark in commerce at a future date (limited to within three years).[21] In the context of esports, the main focus of brand identity would be things like gamertags, handles, or team names. Using gamertags as an example, “use in commerce” for goods could potentially look like using a gamertag in connection with the sale of apparel or computer equipment.[22] For services, “use in commerce” could be participation in video game competitions, production of streams or content, or talent management services connected to the mark.[23] A trademark must be applied for in connection with the goods and/or services it will be used in association with.[24] There must be a demonstration of “use in commerce” for each good and/or service the mark is applied in connection with.[25]

II. Process of Getting A Trademark

A. Trademark Search

Once it has been determined that a mark is properly distinctive, and there has been appropriate use in commerce (or alleged intent to use), the final requirement is that there are no marks currently registered which are the same or similar to your proposed mark, in connection with the same or similar goods and services.[26] This is referred to as “likelihood of confusion,” and the examination looks at the similarity between the proposed marks and currently registered ones, and the similarity of the goods and services.[27] The analysis is a sliding scale; the more similar the marks, the less comparative similarity that needs to be found between goods/services to find “likelihood of confusion.”[28] The more similar the goods/services, the less comparatively similar the marks need to be to find “likelihood of confusion.”[29]

Because trademark protection is a “First to Use” priority system, the first person to use a mark in commerce (or apply for intent to use) will be given the exclusive rights to use that mark.[30] It is crucial that a gamer, team, organization, or clan, conduct a trademark clearance search to ensure that a mark is not prior-used or prior-registered before they start expending time and money building brand value and goodwill with a certain mark or brand identity.

B. Goods and Services Identifications

A trademark cannot be applied for generally; the application must list the particular goods and/or services on or in connection with which the applicant uses, or has a bona fide intention to use, the mark in commerce.[31] Similar goods and services are grouped together into classes, and when applying for a trademark, each classification of goods/services which the mark is used in connection with must be identified. The application fee is based on the number of classes applied for, currently $250 per class for the TEAS-plus application.[32]

To fully complete the registration process, you will need to show an example of use of the mark in commerce in connection with the goods or services it was applied for (this is called a “Specimen of Use”).[33] This means when applying for a trademark, the applicant must ensure they are applying for the correct goods or services which they sell in the marketplace, or “use in commerce,”[34] or else they will not be able to complete registration and risk having their application abandoned.

For a practical example, we can look at esports personality Michael Grzesiek, aka “Shroud.”[35] In seeking protection for the “Shroud” trademark, Grzesiek had to identify all of the goods and services which the “SHROUD”-marks were used (or intended to be used) in connection with and apply for each. Below are some examples of the goods and services which Grzesiek has identified for protection as part of his “SHROUD”-marks.[36]

-

Class 041 – Entertainment Services

-

Arranging, organizing and performing live and online shows featuring video game playing;

-

Production of an ongoing series featuring an esports athlete distributed online;

-

Live show performances and non-downloadable visual and audio recordings being recorded performances featuring video game playing

-

-

Class 016 – Printed Materials

-

Printed materials: namely, posters, event programs, comics, sports trading cards

-

-

Class 028 – Toys or Action figures

-

Toy action figures and toy action figure accessories;

-

Console game controllers

-

-

Class 009 – Electronic Goods

-

Esports-related gaming gloves: namely, virtual reality data gloves

-

The goods and services which Grzesiek has cited in trademark applications can be very instructive to other individuals or entities in the esports field seeking information on how to identify goods or services for their applications. The above goods and services are things which are commonly offered for sale, or promoted in connection with a gamertag or other uniquely source identifying mark, in the esports field. To the extent that anyone has promoted, sold, or offered for sale any of the above goods or services in connection with their gamertag (or any uniquely source identifying mark), they will likely be entitled to federal protection for that mark.

With the above information it becomes clear why it is first very important to be aware of the requirements of a trademark in order to be eligible for protection. Then, conducting a clearance search to ensure your intended mark is free to use before investing time and capital into a mark you may need to change in the future. Next, identify what goods and services the mark is used in connection with (because you will be required to prove that use as part of the registration process). And finally, applying for the mark as soon as possible.

III. The Benefits of Trademark Protection and State of Trademarks in the Esports Field

A. Benefits of Trademark Protection

Although the trademark clearance process may seem onerous, the protection it provides far outweighs any administrative hurdles. Part of the importance of the trademark clearance process is to ensure that your mark is not infringing on any prior marks, which could necessitate your changing of marks or an inability for protection down the line. Below are some examples the benefits of trademark protection.

1. Licensing Agreements

Trademarks allow for rights holders to enter into licensing agreements with third-parties to exploit and monetize their mark, as well as publicly distribute goods without liability.[37] Valid trademark registration can enable teams, athletes, and organizations to sell merchandise featuring their logo through third-party manufacturers and distributors. For example, a t-shirt maker will usually not enter into a licensing deal with an esports athlete or a team to produce merchandise with their logo or mark on it, unless that athlete or team can provide proof of a trademark registration showing their exclusive rights to use that mark.[38] This is because without a trademark registration, that third-party cannot be sure they are not manufacturing and distributing merchandise with someone else’s trademark.

2. Athlete/Individual Bargaining Power

Now more than ever in the esports world, value is in the hands of individual athletes, creators, and personalities. When entering into contract negotiations with teams, organizations, or any entity, if the individual has registered trademark rights (e.g., their gamertag) they can withhold assigning these rights and specifically negotiate for the value of their trademark rights as a licensing deal in addition to the larger agreement. It is important for a player to register before signing with a team because team contracts may include clauses that assign the ownership of any player’s IP to the team itself.

As an important note, it is crucial that an athlete applies for their trademark protection before competing on behalf of a team, as it could cause potential legal issues for who actually owns the mark. As described in Section III(a), trademark rights are a “first to use” system, meaning that the first to use a mark in commerce has the exclusive rights to that mark.[39] If an athlete competes on behalf of a team in a competition without protecting their gamertag and the team uses the athlete’s gamertag as part of the competition, it is possible the team may have just used the gamertag in commerce and that team may then have priority rights for using that mark in connection with gaming competitions.

3. Social Media Takedowns

Brand protection and policing what is distributed to the public in connection with one’s brand are some of the greatest powers of trademark registration. Trademark registration will greatly assist in maintaining and policing the legitimacy of online accounts across social media platforms. Twitter,[40] Instagram,[41] Facebook,[42] YouTube,[43] and Twitch[44] all allow for trademark rights holders to take down accounts infringing on federal trademarks. As the main areas of distribution and consumption of content (and potentially goods and services) in the esports world, it is crucial to have the ability to police and take down infringing uses of your brand across these platforms.

Cheaters and impersonators are also a growing issue in esports.[45] Individuals will attempt to impersonate popular gamers or athletes to trade off the goodwill, status, or value built up in that athlete’s identity. To the extent an athlete’s gamertag is a registered trademark, that athlete would have recourse to takedown any instances of any impersonators trying to distribute any goods or services in connection with that registered trademark. In the context of the esports field, an athlete with a registered trademark gamertag in connection with “entertainment service” could likely prevent, and demand takedown, of any imposters from posting any videos in connection with that mark. However, without a trademark registration, the athlete would have little to no recourse to prevent or demand a takedown of said imposter’s material.

4. Legal Recourse and Remedies

As esports tournaments and events expand, so do the instances of bad actors and contractual disputes.[46] One benefit of a trademark registration is an added legal recourse should there be a contractual dispute or a need to seek remedies for damages or unpaid obligations. For example, in the context of an esports tournament or competition, to the extent that the compensation for an individual or a team’s participation was based on a “licensing fee” for the use of that individual/team’s trademark, a non-payment of any monies owed can be construed as a material breach of contract, and unauthorized use of the mark after that point can potentially be seen as infringement, which could be pursued for damages. Unless contractually documented, monies owed such as a tournament prizes or other compensation for participation can be very difficult to recover. The same could apply to a team’s use of an individual’s mark. Designing compensation around a licensing deal gives an individual or team a potentially very clear and creative avenue for legal recourse if that compensation is threatened. In addition to breach of contract, there could be a federal cause of action for trademark infringement, which could also bring the potential of enhanced damages not available solely through breach of contract.[47]

B. State of Trademarks in the Esports Field

Despite the great benefits of trademarks, the esports field is surprisingly slow to adopt the practice of trademark protection for brands, individuals, organizations, or teams. Taking a look at some examples of statistics and specific high-profile individuals helps elucidate the current issue. While not an exact metric, the popularity and notoriety of personalities in the esports world can be roughly correlated to social media followings, such as their Twitch follower count. Out of the top 100 most followed Twitch streamers, only around one-third have any trademark registrations.[48] Among the top twenty individuals, over half do not have trademark protection, with some unable to ever receive such protection in the future due to their potential marks being ineligible or blocked by prior registrations.[49]

One of the largest gaming personalities in the esports world is Tyler Bevins, aka “Ninja.”[50] Surprisingly, Ninja does not have any trademark protection for the gamertag “Ninja,” and most likely will not receive them. Ninja has attempted to apply for three different trademarks with the word “NINJA” (both as a word, and as that word combined with this logo), and all iterations have been issued refusals because of prior registered marks.[51] Because of the prior registered marks however, Ninja will most likely not be able to receive trademark protection for his name in connection with any multimedia or entertainment goods or services. The implications of this are serious and should be a strong wakeup call to content creators. Despite being an incredibly high profile and recognized individual, Ninja will be unable to have the exclusive rights to his brand name, which could have serious repercussions on his ability to enter into licensing agreements, enforce legal penalties, or police infringement or imposters. Imagine “NIKE” not being able to have the exclusive rights to use the mark “NIKE” in connection with selling shoes. How much would that affect the brand “NIKE”?

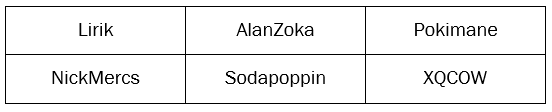

While some high-profile streamers and esports athletes may have trademark application issues, others surprisingly have absolutely zero trademark filings, despite having brands worth millions of dollars in Twitch revenue alone. For example, the following streamers all have over $1 million in yearly Twitch revenue alone, yet have zero trademark filings[52]:

However, on the other side of spectrum are individuals like Grzesiek[53] with 29 filings across a variety of goods and entertainment services; and teams like “Counter Logic Gaming”[54] with two active trademarks across entertainment services; and “100 Thieves”[55] with over 12 registrations across entertainment, apparel, and lifestyle goods and services. With the exclusive rights to their respective trademark, these rights holders are able to enjoy the legal benefits and protections their trademarks afford.

For example, in 2019 the esports team 100 Thieves held a limited-release apparel merchandise drop where they sold out of over $500,000 worth of branded merchandise in under 5 minutes.[56] Trademark rights in the “100 Thieves” mark, in connection with merchandise such as apparel, gave the team the exclusive rights and ability to sell apparel with their mark, and hence the ability to conduct an exclusive limited-edition branded merchandise sale. This example is just one way in which trademark rights can be used to exploit and monetize the value in a player or team/organization’s brand. On the other side of the spectrum however is the lawsuit filed by Riot Games against the esports team “Riot Squad” for trademark infringement of the “RIOT” trademark.[57] This lawsuit highlights the risk of an esports team proceeding with a name they could not protect and infringing on an existing mark.[58]

Conclusion

For any gamer, esports team, or attorney practicing in the field, there should be three takeaways from this article. First, the importance of trademark protection, both in terms of profiting from and protecting your brand. Esports athletes and teams are primarily represented by their gamertag, moniker, or handle. To the extent that a player or team does not have exclusive rights to use that gamertag, moniker, or handle in connection with the goods or services they provide and make money from, this could greatly impact their brand and ability to transact, or even be seen, in the marketplace. Next, trademark registration is a powerful tool for monetizing and capitalizing on the value your brand has accrued (also known as “goodwill”). Trademark rights allow you to enter into exclusive licensing agreements for the use of your mark in connection with the third-party sale of goods and services,[59] as well as specifically negotiate compensation for the use of the trademark in agreements with other organizations, competitions, or events. Finally trademark rights give the ability to police infringing uses of the mark and easily takedown infringement from social media platforms.

Second, a general idea of the trademark process; the requirements for something to be considered a trademark, and the process of applying for a trademark. It may seem intimidating from the outside, but hopefully a brief overview helps to demystify the process. Importantly, trademarks can’t be applied for generally, they must be applied for in connection with goods and/or services which the mark is used in connection with.[60] As part of the trademark application process, you will need to prove you have used the mark “in commerce,” or, sold goods/services in connection with your mark.[61] We discussed a number of common listings for goods and services, which most streamers and esports athletes commonly use their trademarks in connection with.[62]

The final thing which readers should come away from this article with is the shocking lack of trademark protection in this field, especially among the industry’s top earners. The ability to exclusively put out content and merchandise in connection with a gamertag, handle, or name, is an integral part of the business for esports athletes and teams. As such, trademark protection should be an immediate and serious consideration for anyone transacting, or intending to conduct, business in this field. The early effort will pay major dividends in the future, not only in the ability to monetize and capitalize your brand, but also protect and prevent intellectual property or infringement issues. In the enigmatic and wise words of Halo’s Cortana: “I am your shield…I am your sword.”[63]

† Alex Robertson is an expert intellectual property attorney, specializing in trademark and copyright law. For author correspondence please email alex@alexrobertsonesq.com. Copyright © 2021 Alex Robertson.

[1] See Mariel Soto Reyes, Esports Ecosystem Report 0.012632: The Key Industry Companies and Trends Growing the Esports Market Which Is on Track to Surpass $1.5B by 2023, Business Insider (Aug. 3, 2021), https://www.businessinsider.com/esports-ecosystem-market-report.

[2] Alexander Bernevega & Alex Gekker, The Industry of Landlords: Exploring the Assetization of the Triple-A Game, Games & Culture 1 (2021), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/15554120211014151.

[3] See Reyes, supra note 1; see also Justin D. Hovey & Callie A. Bjurstrom, Esports Industry Report, Pillsbury (Dec. 28. 2020), https://www.pillsburylaw.com/images/content/1/4/v8/144736/Esports-Report-FINAL.pdf.

[4] See Tim Lince, Research Finds That Most Major Twitch Streamers Have Not Obtained Registered Trademark Protection for Their Brands, World Trademark Rev. (Aug. 4, 2020), https://www.worldtrademarkreview.com/brand-management/research-finds-most-major-twitch-streamers-have-not-obtained-registered-trademark-protection-their-brands.

[5] See 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

[6] Trademark, Patent, or Copyright, USPTO, https://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/basics/trademark-patent-copyright (last visited Oct 11, 2021).

[7] See 15 U.S.C § 1114.

[8] Assignments, Licensing, and Valuation of Trademarks International Trademark Association, Int’l Trademark Ass’n, https://www.inta.org/fact-sheets/assignments-licensing-and-valuation-of-trademarks (last updated Nov. 9, 2020).

[9] See Marshall Hargrave, Why Goodwill Is Unlike All the Other Intangible Assets, Investopedia (Jan. 24, 2021), https://www.investopedia.com/term/g/goodwill.asp.

[10] Tim Maloney, How Do Esports Teams Make Money?, Roundhill Invs. (Feb. 12, 2020), https://www.roundhillinvestments.com/research/esports/how-do-esports-teams-make-money.

[11] Remington Prods., Inc. v. N. Am. Philips Corp., 892 F.2d 1576, 1580 (Fed. Cir. 1990) (the mark must be considered in context, i.e., in connection with the goods).

[12] Id.

[13] See Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) § 1209.01 (July 2021).

[14] Fact Sheet: Introduction to Trademarks, Int’l Trademark Ass’n, https://www.inta.org/fact-sheets/trademark-strength (last updated Nov. 5, 2020).

[15] See APPLE, Registration No. 3,928,818.

[16] See NETFLIX, Registration No. 3,194,832.

[17] See HOLIDAY INN, Registration No. 592,540.

[18] 15 U.S.C. 1052(e)(1).

[19] See TMEP § 1209.01.

[20] See 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

[21] See 15 U.S.C. § 1051.

[22] 15 U.S.C. § 1127.

[23] Id.

[24] See infra Part III.B.

[25] Id.

[26] See TMEP § 1207.

[27] Id.

[28] Id.

[29] See id.

[30] See TMEP § 901.

[31] See TMEP § 1402.01.

[32] See USPTO Fee Schedule, USPTO (June 25, 2021), https://www.uspto.gov/learning-and-resources/fees-and-payment/uspto-fee-schedule.

[33] See TMEP § 904.

[34] See TMEP § 901.

[35] Shroud, Wikitubia, https://youtube.fandom.com/wiki/Shroud (last visited Oct. 8, 2021).

[36] See SHROUD, Registration Nos. 88,697,996; 88,697,943; 88,697,992; 90,039,324; 90,039,347; 90,039,342.

[37] Trademark Licensing: Everything You Need to Know, Upcounsel, https://www.upcounsel.com/trademark-licensing (last visited Oct. 8, 2021).

[38] Crystal Broughan, The Pros and Cons of Trademark Licensing, Marks Gray (Apr. 12, 2019), https://www.marksgray.com/the-pros-and-cons-of-trademark-licensing.

[39] Widerman Malek, Trademark Law: First to Use v. First to File, Widerman Malek (Apr. 1, 2013), https://www.legalteamusa.net/trademark-law-first-to-use-v-first-to-file.

[40] See Twitter’s Trademark Policy | Twitter Help, Twitter, https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/twitter-trademark-policy (last visited Oct. 11, 2021).

[41] See Instagram Help Center, What If an Instagram Account Is Using My Registered Trademark As its Username?, Instagram, https://help.instagram.com/101826856646059 (last visited Oct. 11, 2021).

[42] See Reporting Trademark Infringements: Facebook Help Center, Reporting Trademark Infringements, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/help/440684869305015 (last visited Oct. 11, 2021).

[43] See Trademark – YouTube Help, Google, https://support.google.com/youtube/answer/6154218?hl=en (last visited Oct. 11, 2021).

[44] See Twitch.tv – Trademark Policy, Twitch.tv, https://www.twitch.tv/p/en/legal/trademark-policy (last visited Oct. 11, 2021).

[45] See Rob LeFebvre, ‘Overwatch’ Streamer Destroys His In-Game Imposter, Engadget (Feb. 22, 2017), https://www.engadget.com/2017-02-22-overwatch-streamer-destroys-imposter.html.

[46] See Alex Nealon, Riot Games Rioting Over Esports Team’s Trademark Infringement, Lexology (Feb. 6, 2020), https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=9680ca84-769b-41e0-9b48-498f915eb2cf; Christina Settimi, Fortnite Star Tfue Settles Dispute With FaZe Clan, Ending Esports’ First Major Employment Lawsuit, Forbes (Aug. 26, 2020, 1:59 PM), https://www.forbes.com/sites/christinasettimi/2020/08/26/fortnite-star-tfue-settles-dispute-with-faze-clan-ending-esports-first-major-employment-lawsuit.

[47] See 15 U.S.C. § 1117.

[48] See Top 100 Most Followed Twitch Accounts (Sorted by Followers Accounts), Socialblade, https://socialblade.com/twitch/top/100 (last visited Oct. 11, 2021).

[49] See Lince, supra note 4.

[50] See Ben Gilbert, Ninja Just Signed a Multi-Year Contract That Keeps Him Exclusive to Amazon-Owned Twitch, Bus. Insider (Sept. 10, 2020, 1:52 PM), https://www.businessinsider.com/ninja-signs-multi-year-exclusivity-contract-with-amazon-twitch-2020-9.

[51] See NINJA, Registration Nos. 88,206,561; 88,206,555; 88,481,530.

[52] See Lince, supra note 4.

[53] See sources cited supra note 36; see also Shroud, Inc. Trademarks, Trademarkia, https://www.trademarkia.com/company-shroud-inc-5310540-page-1-2 (last visited Oct. 11, 2021) (showing 29 results).

[54] COUNTER LOGIC GAMING, Registration No. 6,209,609; CLG, Registration No. 5,457,919.

[55] LOS ANGELES THIEVES, Registration Nos. 90,303,274; 90,303,297; 90,303,313; 90,303,327; 90,303,337; 90,303,348; HONOR AMOUNG THIEVES, Registration No. 90,269,452; 100 THIEVES, Registration Nos. 6,079,647; 5,689,916; 5,514,617; 5,976,650; 100T, Registration No. 5,785,576.

[56] See Andrew Webster, How 100 Thieves Became the Supreme of E-Sports, The Verge (Sept. 5, 2019 8:30 AM), https://www.theverge.com/2019/9/5/20849569/100-thieves-nadeshot-esports-supreme-drake.

[57] Nicole Carpenter, Riot Games Files Lawsuit Against Esports Organization Over ‘Riot’ Trademark. Polygon (Oct. 10, 2019, 11:37 AM), https://www.polygon.com/2019/10/10/20908027/riot-games-copyright-trademark-lawsuit-riot-squad.

[58] Id.

[59] See Trademark Licensing, supra note 37.

[60] See TMEP § 901.

[61] Id.

[62] See supra Part II.B.

[63] HaloBaseLegend, Halo 3 – First Announcement Trailer [HD] – E3 2006, YouTube (June 14, 2012), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9Ezd2FqxAU&t=53s.