by Jullian Haley†

Introduction[1]

Unlike the established sports industry, esports is the undeveloped wild west.[2] While games such as Quake, Counter Strike, and World of Warcraft provided a foundation for the early esports scene, present-day professional esports dwarf their predecessors in both scale and scope. Today, professional esports players can be highly compensated for both their in-game expertise and the exposure they provide to sponsors and their team.[3] But where the prize money stops short, match-fixing begins.[4]

Like traditional sports, the betting scene surrounding professional esports enables fans to place bets on the outcome of matches and tournaments. If an individual knows a certain outcome to a future game or match, then betting on that match could be extremely lucrative. The classic example is when a player on an esports team bets against himself and voluntarily loses or “throws” a match resulting in the player receiving a lot of money.[5]

Although esports is a lucrative business, only players on top tier teams earn a considerable salary.[6] This imbalance leaves many mid-to-low tier professionals with the attractive option of voluntarily losing games to earn vastly more money than they may make throughout their professional career.[7]

Currently, there are few serious repercussions for match-fixing.[8] However, change is on the horizon; the FBI has established a sports betting unit that investigates claims of match-fixing in CSGO’s North American Mountain Dew League based on evidence submitted by the Esports Integrity Commission (“ESIC”).[9]

Previous regulation and litigation surrounding esports in the United States concentrated primarily on the civil and business-oriented areas of the law.[10] The establishment of the FBI’s Sports Betting Investigative Unit portends possible federal criminal prosecution of match-fixing, the threat of which may change the landscape of competitive integrity in esports. Given that the inherent interstate nature of internet-based esports allows for broad federal jurisdiction, federal prosecution over match-fixing has become a real threat.[11]

Part I of this article looks at the history of esports match-fixing and criminal charges. Part II focuses on the federal crimes that esports professionals are most likely to be charged under and the reasoning behind each strategy. Part III looks at the impact of juvenile status in charging federal crimes. Finally, Part IV looks at alternative solutions to federal prosecution that would aid in preventing match-fixing from becoming mainstream in esports.

I. Esports Betting and Match-fixing

As long as there is betting, there is match-fixing. Professional esports has a strong gambling scene similar to professional sports.[12] However, esports also has a long history of underpaid professionals throwing games for monetary gain.[13] With intrastate sports betting and mobile sports betting becoming legalized after the United States Supreme Court’s decision in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association,[14] the ability for mass betting on esports has broadly expanded.[15] This broad expansion has the possibility of extending the avenues in which match-fixing enterprises can earn money.

A. Past Examples of Match-Fixing and Criminal Charges

This subsection unpacks increasingly more complex esports match-fixing examples from individual efforts to fully functional criminal enterprises. The focus will primarily be on the two clear examples of law enforcement bringing criminal charges against individuals involved in esports match-fixing. These examples provide insight into the different angles that the FBI might consider when investigating the professionals involved in the North American Mountain Dew League match-fixing. The different examples will be ordered in levels of criminal sophistication from least to most.

1. Australian Friends and Their Match-fixing

In comparison to a more developed professional esports scene with investment opportunities and sponsorships, the Australian scene with its lack of capital creates a weak mid-tier professional scene that makes it ripe for match-fixing incidents.[16] On August 23, 2019, Victoria Police released a press statement announcing they had arrested six people regarding suspicious betting activity surrounding an esports league.[17] Around five matches were thrown with over twenty bets placed on those matches.[18]

Officials interviewed the defendants about “engaging in conduct that corrupts or would corrupt a betting outcome of event or event contingency, or use of corrupt conduct information for betting purposes.”[19] Five charged individuals faced up to 10 years in prison. The level of sophistication in this scheme was simple and all of the players involved knew each other. “They had gone to the same high school and university. They had no prior entanglements with police[.]”[20]

2. 2015 Korean StarCraft 2 Match-Fixing

The South Korean StarCraft professional scene is also rife with scandal. More sophisticated than the Australian incident, the web of individuals involved was vast and deeply rooted in the esports scene. In 2010, the web of corruption went beyond the players and involved the broader esports scene, which included coaches, journalists and esports personalities.[21]

Leading teams have been accused of intentionally losing matches and leaking information to gambling syndicates…Retired pro gamers are said to have made the initial contact between the gambling organisations and the teams. Match commentators and reporters are also said to be involved, while team coaches are alleged to have accepted money for changing their team’s line-ups.[22]

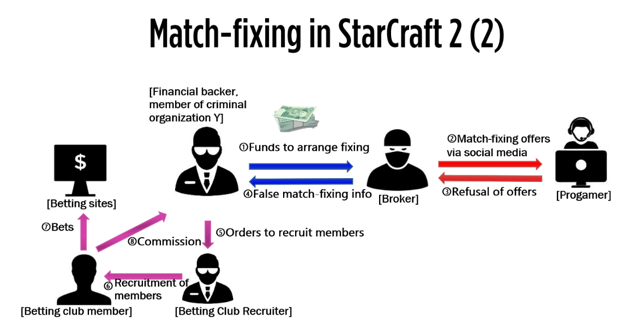

In 2015, scandal again hit the Korean professional StarCraft 2 scene.[23] South Korean police arrested twelve individuals.[24] According to a translation of an organization’s press release, members of a criminal organization paid these professional players to throw multiple matches, which were consequently bet on illegally.[25] Soon after, the Changwon Regional Prosecution Service investigated the match, detailing the “network of players, brokers, financial backers and illegal betting sites.”[26]

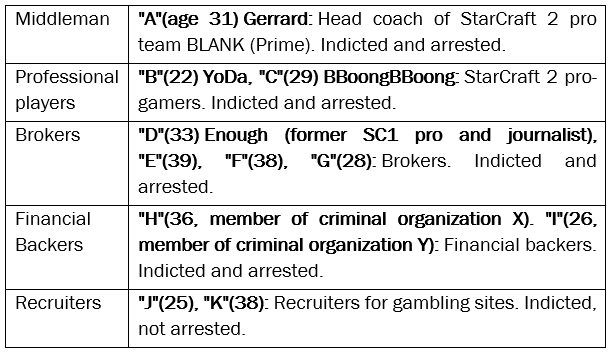

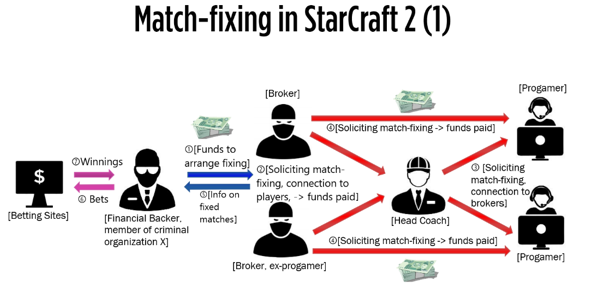

These are the players, the middlemen, the brokers, and the financial backers.[27]

In this situation, two players threw the five games, YoDa and BBoongBBoong.[28] Gerrard made the introductions, acting as the middleman.[29] He convinced the players to manipulate the results of the match and either introduced the players to brokers or directly solicited the match-fixing himself.[30]

The brokers approached the players in a variety of ways. The prosecutor’s report mentioned three methods used. The first was to pose as a sponsor.[31] “Brokers approached under the guise of being sponsors. Acquired services through [Gerrard], then approached players directly. They later forced match-fixing services through extortion.”[32] In this specific case, after the first match-fix through Gerrard, E and F contacted the players directly, and, by threatening exposure of the match-fixing, manipulated additional matches without paying the players.[33]

Enough, an ex-pro-gamer and gaming journalist executed the broker’s second method.[34] His status in the community, his connections with the pro scene, and his relationship with Gerrard and YoDa allowed Enough to approach them and arrange match-fixing for a large fee.[35]

The broker’s third method was G’s attempt to solicit match-fixing through social media offers.[36] G would try to “blindly offer match-fixing opportunities to pro-gamers or their acquaintances through Facebook posts.”[37] Although this method was not useful nor successful in actually recruiting professional players to throw matches, the broker was able to receive thousands of dollars from “financial backers under the premise of ‘operating funds.’”[38]

The financial backers in this situation were all members of organized crime groups in Korea.[39] The two financial backers in this enterprise employed two different methods.[40] In the first method, the financial backer, or H, promised the broker funds to arrange the manipulation, and then used the illegal gambling websites to bet on the matches.[41] The winning funds were then recycled into further match-fixing.[42]

The second method consisted of the financial backer giving funds to the broker to arrange the match-fixing.[43] Once the financial backer received information on matches to be fixed, he made gambling site recruiters go to net cafes and recruit members for a betting club.[44] The financial backer received a 30% commission from what ended up being fifty club members.[45]

On March 31, 2016, multiple parties in this incident received their sentence.[46]

Gerrard, YoDa, and BBoongBBoong were sentenced to eighteen months in prison, but had their sentences suspended for three years. Former pro-gamer Enough who acted as a broker received a two-year sentence, suspended three years . . . The other brokers and financial backers involved received sentences between 10 and 18 months, also suspended.[47]

The illustrations created by the Changwon District Prosecutors’ Office below show how the money moved in these match-fixing schemes.

B. FBI Takes Action Towards MDL Match-fixing

A recent interview with ESIC’s Commissioner Ian Smith highlighted that the FBI was looking into a string of match-fixing incidents within the ESEA Mountain Dew League.[48] The Mountain Dew League (MDL), also known as ESEA Premier, is the league right below the ESL Pro League, one of the highest ranked CS:GO professional circuits in the world. The winners of the MDL are given the opportunity to move up to the ESL Pro League and the MDL players are considered the feeder pool for the more well-regarded professional teams. Not only are the matches between the MDL teams regularly streamed on platforms like Twitch and YouTube, but they are also regularly posted on betting websites.

Smith draws a contrast between Australia and the MDL match-fixing, saying that Australia’s match-fixing was just a group of players organizing the fixings.[49] Regarding the MDL match-fixing, Smith mentions that “in North America it’s much more serious and it is what [we] would describe as classic match fixing. [The] players [are] being bribed by outside betting syndicates in order to fix matches rather than players . . . and it’s been going on for longer.”[50] As such, Smith mentions that ESIC is working with the FBI’s newly created Sports Betting Investigative Unit—created to respond to the legalization of sports betting in the United States as a result of Murphy.

With the introduction of Murphy and Covid-19, esports betting in the United States has blown up. Given the evidence that ESIC has gathered, along with the possibility that esports betting can be readily abused, it only makes sense that the FBI would investigate.

II. Federal Crime Selection: Pros and Cons to Prosecution Methods

With the FBI looking into the MDL match-fixing, it would be valuable to look at the relevant federal crimes that could be used to prosecute the match-fixing defendants. This section focuses on different approaches that the FBI might consider instead of looking to see if the individual players fulfill the elements of the individual criminal statutes.

A. Traditional Match-fixing Laws and Their Nonapplication to Esports

Federal crimes targeting strict definition match-fixing are narrow laws and have been hardly found to be useful over the past century. Prior to the establishment of RICO, there was the Federal Wire Act (1961),[51] a statute targeting organized crime, and the Sports Bribery Act (1964),[52] a statute focusing on bookmaking and match-fixing. The Sports Bribery Act is incredibly inefficient, having only generated sixteen reported decisions, one pending indictment, and a total of zero decisions implicating professional team sports.[53]

With the recent legalization of sports betting in the United States, these statutes deserve a second look. The Federal Wire Act essentially bans interstate “wire communication (internet)” in betting or wagering on any sporting event or contest where the transmission of the communication would entitle the recipient to receive money as a result of the betting or for information assisting in the placing of bets or wagers.[54] However, it is extremely limited in scope due to its straightforward focus on sports events and contests, as ruled by two Federal Courts of Appeals.[55] Similarly, in the recent New Hampshire decision, the First Circuit focused on matching the Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel’s 2011 opinion that the Wire Act only applied to sports gambling.[56]

Since the holdings that limit the Federal Wire Act focus purely on sports events and contests, it is unlikely that it would apply to esports despite their similarities. Given the strict treatment that the Federal Wire Act has been given, limiting its power to pure sport contests, it is likely that the Sports Bribery Act would also not apply for similar reasons.

B. The Use of RICO in Broad Application to the MDL Criminal Enterprise

Instead of the specific requirements under the Federal Wire Act and Sports Bribery Act that necessitate encompassing esports within the narrow definition of ‘sporting contest,’ the use of more generalized federal crime statues is entirely more likely in these circumstances due to the broader application of these laws.[57] The use of a federal action under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act could be a starting point for federal prosecutors.[58]

RICO, although initially intended to clamp down on gang activity and its infiltration into legitimate businesses, applies well to the situation at hand.[59] RICO “provides powerful criminal penalties for persons who engage in a ‘pattern[60] of racketeering activity’ or ‘collection of an unlawful debt’ and who have a specified relationship to an ‘enterprise’ that affects interstate or foreign commerce.”[61]

The number of crimes covered under “racketeering activity”[62] and what can be considered an “enterprise” makes RICO broadly applicable.[63] “Under the RICO statute, ‘racketeering activity’ includes state offenses involving murder, robbery, extortion, and several other serious offenses . . . and more than one hundred serious federal offenses.”[64] Similarly, an enterprise is broadly defined as “includes any individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity.” In this situation, the crimes charged would be the relevant crimes in subsections (1)(A) and (1)(B):[65]

18 U.S.C. Section 1961(1)(A): gambling, bribery, extortion as charged under state law and punishable by imprisonment for more than one year; or

The following relevant acts under 18 U.S.C. Section 1961(1)(B): 18 U.S.C. Section 224 (sports bribery); Section 1084 (relating to the transmission of gambling information); section 1341 (mail fraud); section 1343 (wire fraud); section 1952 (relating to racketeering), section 1955 (relating to the prohibition of illegal gambling businesses), section 1956 (relating to the laundering of monetary instruments), section 1957 (relating to engaging in monetary transactions in property derived from specified unlawful activity).

This article will not focus on an analysis of whether the MDL match-fixing fulfils the elements of the individual RICO crimes, but will instead focus on the likelihood of a federal prosecutor bringing a RICO action against these teams.

Looking at the list of crimes elaborated above, and considering that a pattern of only three crimes is required, it is likely that the prosecutor could find that RICO is applicable against the MDL match-fixing enterprise and its individuals, especially given the longer timeline of the match-fixing and higher frequency of matches.

The considerations that a federal prosecutor would have to take are plenty, but a prosecution like this would fulfill many of the considerations required prior to seeking an indictment.[66] RICO can help combine the related offenses which would have to otherwise be prosecuted inefficiently and separately. Additionally, RICO would allow for a reasonable expectation of forfeiture proportionate to the underlying criminal conduct.[67]

The forfeiture aspect is valuable in this situation due to the specific factual scenario at play.[68] Much like the Korean StarCraft match-fixing, there are financial backers that not only pay the professional players to throw the match, but they also use their own money in match-fixed bets. The federal government’s main focus in this prosecution is unlikely to be on the individual players, but the financial backers who organized and funded the match-fixing criminal enterprise. Given the relatively young ages of the professional players and their value in providing information about the financial backers, the best strategy for the younger players would be to provide information regarding those financial backers in exchange for a reduced sentence.

C. Individual Crimes

Considering the strict requirements that the Department of Justice has to follow before a prosecutor can file a RICO case, an alternative action would be to charge the individuals with the underlying individual RICO crimes, but not under the RICO Act. It could be quicker and less work to piecemeal prosecute each defendant, although you forgo the ability for forfeiture under RICO.

Given the substantial level of evidence that ESIC had submitted to the FBI, evidence that clearly outlines the specific actions of individuals and their degree of involvement in the conspiracy, federal prosecutors can be expected to quickly charge the individuals after a brief investigation.

For a clearer perspective and a recent example, the 2021 United States Capitol Attack is instructive. Politics aside, this is an example of a complex federal prosecution of hundreds of individuals tied to a singular event, and yet individualized prosecutions are being brought forth based on evidence found that is unique to each individual.

For example, as of June 11, 2021, 465 individuals have been arrested in connection with the attack.[69] Within that 465, 440 were charged with entering or remaining in a restricted building or grounds. One-hundred thirty individuals have been charged with assaulting, resisting, or impeding officers.[70] Forty individuals have been charged with using a deadly weapon against an officer.[71] Thirty-five defendants have been charged with conspiracy, twenty-five charged with theft of government property, and more than thirty charged with destruction of government property.[72]

The federal government pieced together evidence against these individuals through its extensive campaign.[73] They received “more than 270,000 digital media tips, 15,000 hours of surveillance and body-worn camera footage, with 80,000 reports and 93,000 attachments related to law enforcement interviews.”[74]

Similarly, in this case, the FBI could pick and choose individual crimes to charge based on the information that they received from ESIC. This information includes “corroborating evidence from discord, various chat logs, screenshots, and recordings of players.”[75] These chatlogs could matchup with specific performance issues in specific games where it was suspected matches were thrown. Additionally, the FBI would have the ability to follow the money and trace it as it moves from the betting syndicates to the individual players.

III. The Impact of Juvenile Status in Federal Prosecution

This is a situation where the age of the professionals is significant. In the MDL circuit—where many players are on the cusp of reaching the highest tier of professional play—some players are juveniles. Their juvenile status plays a large role in how they would be treated under a federal prosecution charge.

In the United States, juveniles are treated very differently from the adults in the criminal justice system.[76] Many jurisdictions have juvenile courts which focus on rehabilitating the juvenile criminal offender in hopes that they can remedy the underlying issues that brought these offenders to court.[77] This includes massively reduced sentencing, more probation activity and deferred dispositions with treatment alternatives that try their best to support rehabilitation.[78]

Similarly, the federal government hesitates before charging a juvenile with a federal crime. The courts define a juvenile as “someone who committed a federal crime before the age of 18 and who has not yet reached the age of 21 at the time charges are brought.”[79] To successfully bring a federal charge against a juvenile, you need to file a juvenile information and a certification on the grounds that warrant federal jurisdiction over the juvenile.[80]

The certification is a preventative barrier to juvenile federal prosecution. The U.S. Attorney must “certify either that: (1) the state or juvenile court does not have jurisdiction or refuses to assume jurisdiction over the juvenile as to the alleged conduct; (2) the state cannot provide juvenile services; or (3) the offense charged is a felony crime of violence or is one of the Title 21 offenses or federal firearms statutes enumerated in the JDA, and there is a substantial federal interest in the case to justify the exercise of federal jurisdiction.”[81]

In many cases, states have jurisdiction over these types of federal crimes[82] and they often can provide juvenile services.[83] All of these match-fixing crimes are not crimes of violence. It is likely that the case would be dismissed, unless charges are brought after the juvenile turns twenty-one or unless they continue committing the match-fixing past their eighteenth birthday.[84]

The FBI is more likely to offer either larger deals or dismissals to juvenile offenders in hopes of retaining information about the more significant financial backers, who in this case are the betting websites and criminal syndicates who are setting up the throws.

IV. Possible Additional Alternative Solutions for Match-fixing

This subsection explores possible solutions to stifle match-fixing in esports before it can be normalized.[85]

A. Educating Stakeholders

The relevant parties in esports need to educate themselves more. Stakeholders in professional esports might include team owners, tournament organizers, video game creators and professional players. Education about match-fixing’s possible impact on the integrity of esports is important. Perceptions about the legitimacy of semi-professional leagues have dipped due to continuous match-fixing in relatively unregulated regions.[86]

B. Whistleblowing Incentives

Tournament organizers and teams could issue rewards for players who blow the whistle when they catch a hint of match-fixing impropriety. For example, the United States Security and Exchange Commission has a whistleblower program that is famous for the generous rewards that the whistleblower receives when they report possible securities violations.[87] A similar system, set up through a commission like ESIC, could help prevent the creation of a sophisticated match-fixing system.

C. Stiff Visible Punishments

Stiff visible punishments can be an effective deterrent towards match-fixing. In the iBuypower incident, Valve’s strict punishment of an indefinite ban on those professional players led to no obvious match-fixing among the highest level of CS:GO play.[88] Although this might not present enough of a threat for the semi-professional level, where the gains outweigh the losses in fixing matches, federal prosecution could be the kick that stops this corruption.

However, ESIC’s recent actions could present an alternative to federal prosecution that would specifically target the semi-professional scene with realistic visible harsh punishments. In late August 2021, ESIC launched their “Transparency Initiative” to better show the world its processes in investigating and sanctioning professional esports players.[89] Along with the release of their Transparency Initiative, ESIC gave an update regarding their progress in the MDL investigation.[90] ESIC sanctioned three players and provided virtually industry-wide bans as short as 111 days to as long as 5 years.[91]

Although this might be effective towards professional and semi-professional players, it doesn’t present enough of a threat to the criminal enterprises that were part-and-parcel of the MDL match-fixing, rendering it a partially effective solution.[92] However, ESIC seems aware of their limited role as an integrity commission and works together with law enforcement so the relevant government bodies can impose the criminal penalties on the responsible organized crime groups and foreign betting syndicates.[93]

Conclusion

Esports betting is a growing industry and has the potential for similar growth of illegal activity if not curtailed. With growing mobile betting and esports’ larger role in online gambling, billions of dollars depend on the actions of these professional players. Semi-professional players have a large incentive to match-fix due to the massive benefits of match-fixing. Federal prosecution is the punishment or threat needed to prevent large scale match-fixing. Given the many crimes that prosecutors can use to charge players, this threat along with the alternative solutions should stop match-fixing in esports before it successfully enters the mainstream.

[†] Jullian Haley is a Deputy Prosecuting Attorney at the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office. For author correspondence please email Jullian.Haley@gmail.com. Copyright © 2021 Jullian Haley.

[1] Integrity and Fair Play, Blog.Counter-Strike.net (Jan. 26, 2015), https://blog.counter-strike.net/index.php/2015/01/11261.

[2] Leo Lewis, Esports: The Wild West of Gaming That Investors Can’t Ignore, Financial Times (Sept. 20, 2018), https://www.ft.com/content/b3359c2e-bceb-11e8-8274-55b72926558f.

[3] Pavle Marinkovic, Esports Pro Gamers: How Much Do They Earn?, Super Jump Magazine (July 8, 2020), https://superjumpmagazine.com/esports-pro-gamers-how-much-do-they-earn-f03a1d047190.

[4] See Elias Andrews, The Potential for Esports Match-Fixing Is as High as Ever, The Sports Geek (Apr. 18, 2020, 8:00 AM), https://www.thesportsgeek.com/blog/esports-match-fixing-potential-high-as-ever; see also Chris Godfrey, ‘It’s Incredibly Widespread’: Why Esports Has a Match-Fixing Problem, The Guardian (July 31, 2018), https://www.theguardian.com/games/2018/jul/31/its-incredibly-widespread-why-esports-has-a-match-fixing-problem.

[5] See Gökhan Çakır, What is Match-Fixing in Esports?, Dot Esports (Apr. 17, 2021, 12:52 PM), https://dotesports.com/general/news/what-is-match-fixing-in-esports.

[6] Andrews, supra note 4.

[7] Id.

[8] Çakır, supra note 5.

[9] ESIC focuses on working with stakeholders to apply ethical standards in regular sports to the esports professional scene. For more information, see www.ESIC.org/about. For a list of ESIC’s esports investigations, see Open Investigations Register, ESIC (Aug. 2021), https://esic.gg/open-investigations-register; Slash32, “It’s Players Being Bribed By Outside Betting Syndicates” – ESIC Ian Smith // Interview, YouTube (Mar. 31, 2009), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DjhnRKBaNwA (hereafter “Ian Smith Interview”).

[10] For more subject areas typically dealt with by law firms dealing in esports see Patrick J. McKenna, ESports Practice Becoming a Lucrative Micro-Niche for Law Firms, Thomson Reuters: L. Exec. Inst. (Mar. 28, 2019), https://web.archive.org/web/20201126094229/https://www.legalexecutiveinstitute.com/micro-niche-esports-practice.

[11] For the proposition that wire fraud is a catchall federal crime often prosecuted due to its ease in proving the elements, see Darryl A. Goldberg, Don’t Underestimate The Gravity of Wire Fraud Charges, Goldberg Defense (Sept. 28, 2016), https://www.goldbergdefense.com/blog/2016/09/dont-underestimate-the-gravity-of-wire-fraud-charges.

[12] See sources cited supra note 4.

[13] See sources cited supra note 4.

[14] 138 S. Ct. 1461 (2018).

[15] David Hoppe, These Four States Are on Track to Legalize Esports Betting, Gamma L. (Mar. 9, 2020), https://gammalaw.com/these-four-states-are-on-track-to-legalize-esports-betting.

[16] Nino Bucci & Sarah Curnow, Australian Esports Criminal Investigation Reveals Video Game Industry is Ripe for Corruption, ABC News (Sept. 23, 2019), https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-09-24/fears-world-of-esports-is-ripe-for-corruption/11521008.

[17] Six People Arrested Re Esports Investigation, Victoria Police (Aug. 22, 2019), https://web.archive.org/web/20190827114718/https://www.police.vic.gov.au/six-people-arrested-re-esports-investigation.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] Stoyan Todorov, Australian Men Face up to 10 Years Imprisonment for Esports Match-Fixing, Gambling News (May 4, 2020), https://www.gamblingnews.com/news/australian-men-face-up-to-10-years-imprisonment-for-esports-match-fixing.

[21] Oli Welsh, Betting Scandal Hits Korean StarCraft, Eurogamer (Apr. 14, 2010), https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/betting-scandal-hits-korean-starcraft-scene.

[22] Id.

[23] Emanuel Maiberg, 9 People Have Been Arrested for Fixing ‘StarCraft’ Matches, VICE (Oct. 19, 2015, 6:20 AM), https://www.vice.com/en/article/3dkxew/9-people-have-been-arrested-for-fixing-starcraft-matches; see also Wesley Yin-Poole, Korean Starcraft Rocked by Another Match-Fixing Scandal, Eurogamer (Oct. 19, 2015), https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2015-10-19-korean-starcraft-rocked-by-another-match-fixing-scandal.

[24] Yin-Poole, supra note 23.

[25] Maiberg, supra note 23.

[26] Waxangel, Match-Fixing: Prosecutor’s Report, TL.net (Oct. 19, 2015), https://tl.net/forum/starcraft-2/496889-match-fixing-prosecutors-report. For the original Korean version, see StarCraft 2 Match-fixing Case Investigation Results, Changwon District Prosecutors’ Office (Oct. 19, 2015), https://web.archive.org/web/

20151126155441/http:/www.spo.go.kr/changwon/notice/press/press.jsp?mode=view&article_no=605393&pager.offset=0&board_no=2&stype=.

[27] Waxangel, supra note 26.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] Id.

[31] Id.

[32] Id.

[33] Id.

[34] Id.

[35] Id.

[36] Id.

[37] Id.

[38] Id.

[39] Id.

[40] Id.

[41] Id.

[42] Id.

[43] Id.

[44] Id.

[45] Id.

[46] Lee Jeong-hoon, ‘스타크2’ 승부조작 집행유예…법원 “이번만 선처, Yonhap News Agency (Mar. 31, 2016, 3:24 PM), https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20160331136100052. For the English translation, see Waxangel, PRIME Match-Fixers Given Suspended Sentences, TL.net (Mar. 31, 2016), https://tl.net/forum/starcraft-2/506723-prime-match-fixers-given-suspended-sentences.

[47] Waxangel, supra note 46.

[48] Ian Smith Interview, supra note 9.

[49] Id.

[50] Id.

[51] 18 U.S.C. §§ 1081–84.

[52] 18 U.S.C. § 224.

[53] John Holden & Ryan Rodenberg, The Sports Bribery Act: A Law and Economics Approach, in Florida State University Symposia, https://chaselaw.nku.edu/content/dam/chase/docs/lawreview/symposia/8_Rodenberg_Sports%20Bribery%20Act.pdf; see also John Holden and Ryan M. Rodenberg, The Sports Bribery Act: A Law and Economics Approach, 42 N. Ky L. Rev. 453, 460 (2016).

[54] See 18 U.S.C. § 1081.

[55] See In re Mastercard Int’l, 313 F.3d 257, 262-63 (5th Cir. 2002); see also N.H. Lottery Comm’n v. Rosen, 986 F.3d 38 (1st Cir. 2021); see also William Moschella, Scott Scherer, Mark Starr, Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, Wire Act Ruling a Win for iGaming and Lotteries, Status Quo for Sports Betting—for Now, JD Supra (Jan. 28, 2021), https://www.jdsupra.com/legalnews/wire-act-ruling-a-win-for-igaming-and-9102417 (explaining that the recent New Hampshire decision finds that “the Wire Act applies only to gambling activities on sporting events and does not prohibit other forms of gambling conducted over the internet—including online casino gaming (iGaming) or online lotteries (although iGaming or online lotteries may be prohibited by other laws in various states)”).

[56] See generally, Rosen, 986 F.3d 38. Also, the Department of Justice’s Opinion came to that conclusion based on the text, legislative history, and underlying policy purposes of the Act.

[57] For more background information on RICO, see U.S. Dep’t of Just., Just. Manual § 9-110.100 (2018) (hereafter “Justice Manual”).

[58] See 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961–68.

[59] Andrew Boggs, Integrity and Esports | Cheating in Competitive Games (Aug. 7, 2021), https://www.strafe.com/esports-betting/news/integrity-and-esports-cheating-in-competitive-games.

[60] Id.

[61] U.S. Dep’t of Just., Crime & Gang Sec., Criminal RICO: 18 U.S.C. §§ 1961-1968 A Manual for Federal Prosecutors 15 (2016), https://www.justice.gov/archives/usam/file/870856/download (hereafter “Criminal RICO”).

[62] See 18 U.S.C. § 1961(1).

[63] See 18 U.S.C. § 1961(4).

[64] See 18 U.S.C. § 1961 for full list of offenses.

[65] The other subsections concern labor and union organizations, securities fraud, dealing with controlled substances, the Currency and Foreign Transactions Reporting Act, and the Immigration and Nationality Act and as such they do not apply.

[66] Justice Manual, supra note 57, § 9-110.310 (considerations prior to seeking indictment).

[67] Id.

[68] Criminal RICO, supra note 61, at 220 (“[RICO’s forfeiture statutes] authorize the forfeiture of not only proceeds and interests obtained by the defendant from any racketeering activity but also all of the defendant’s various interests in the charged ‘enterprise.’”).

[69] Clare Himes, Cassidy McDonald & Eleanor Watson, What We Know About the “Unprecedented” Capitol Riot Arrests, CBS News (June 11, 2021, 6:36 PM), https://www.cbsnews.com/news/capitol-riot-arrests-latest-2021-06-11.

[70] Id.

[71] Id.

[72] Id.

[73] Id.

[74] Id.

[75] Ian Smith Interview, supra note 9.

[76] Youth in the Justice System: An Overview, Juvenile L. Ctr., https://jlc.org/youth-justice-system-overview.

[77] Juvenile Justice, Youth.gov, https://youth.gov/youth-topics/juvenile-justice.

[78] Id.

[79] 18 U.S.C. § 5031; see also Criminal RICO, supra note 61, at 461.

[80] 18 U.S.C. § 5032; see also Justice Manual, supra note 57, § 9-8.110.

[81] Criminal RICO, supra note 61, at 462.

[82] The state courts have jurisdiction over similar state crimes.

[83] For match-fixing alternatives, look at the services provided at sentencing to the Korean StarCraft players who match-fixed in 2010, see Ambasa, BW Matchfixing Sentencing, TL.net (Oct. 22, 2010), https://tl.net/forum/community-news-archive/162856-bw-matchfixing-sentencing.

[84] Criminal RICO, supra note 61, at 464, 471.

[85] Suggestions in this section are adopted from the symposium by authors Holden and Rodenberg, see supra note 53, where the authors focus on how to make the Sports Bribery Act more effective, but the suggestions broadly apply in esports match-fixing as well.

[86] For match-fixing in the CIS region, see Rohan Samal, ESIC finds potential Matchfixing and Betting Fraud is CIS RMR Event, Esports.gg (June 9, 2021), https://esports.gg/news/cs-go/esic-cis-rmr-matchfixing. For match-fixing in China, see Richard Lewis, Match Fixing In Chinese CS:GO, YouTube (July 4, 2017), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y2Dz3Nwn-v0.

[87] Press Release, Sec. Exch. Comm’n, SEC Awards $22 Million to Two Whistleblowers (May 10, 2021), https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2021-81 (“Whistleblowers may be eligible for an award when they voluntarily provide the SEC with original, timely, and credible information that leads to a successful enforcement action. Whistleblower awards can range from 10 percent to 30 percent of the money collected when the monetary sanctions exceed $1 million.”).

[88] Richard Lewis, New Evidence Points to Match-Fixing at Highest Level of American Counter-Strike, Dot Esports (Jan. 16, 2015, 4:03 PM), https://dotesports.com/general/news/match-fixing-counter-strike-ibuypower-netcode-guides.

[89] Press Release, Esports Integrity Comm’n, ESIC Launches ‘Transparency Initiative’ to Bolster Visibility of Investigative Work and Outcomes (Aug. 21, 2021), https://esic.gg/press-release/esic-launches-transparency-initiative-to-bolster-visibility-of-investigative-work-and-outcomes.

[90] Press Release, Esports Integrity Comm’n, ESIC Update Regarding NA ESEA Match-Fixing Investigation (Aug. 23, 2021), https://esic.gg/press-release/esic-update-regarding-na-esea-match-fixing-investigation.

[91] Id. These bans essentially prevent the sanctioned players from playing in any tournaments hosted by the ESIC partners, which cover the vast majority of the professional Counter Strike scene.

[92] Press Release, Esports Integrity Comm’n, ESIC Update Regarding NA ESEA Match-Fixing Investigation (Aug. 23, 2021), https://esic.gg/press-release/esic-update-regarding-na-esea-match-fixing-investigation.

[93] Id.